“We are limited in South Africa because our democratic Government

inherited a debt which at the time we were servicing at the rate of 30

billion rand a year. That is thirty billion we did not have to build

houses, to make sure our children go to the best schools, and to ensure

that everybody has the dignity of having a job and a decent income.”

Nelson Mandela

Considering the socioeconomic complications of post-apartheid South Africa, there isn’t much talk about the details of the transition from apartheid state to democracy. Many in South Africa and around the world still ask: What exactly led the National Party to give up power? Was it the political protests? The global economic sanctions? The massive debt accumulated by the apartheid state? And why hasn’t progress been more palpable for the millions of poor South Africans who fought for freedom? Is government corruption at fault? The HIV/AIDS epidemic? The fear of the country turning into “another Zimbabwe” or the bureaucratic realities of land reform ?

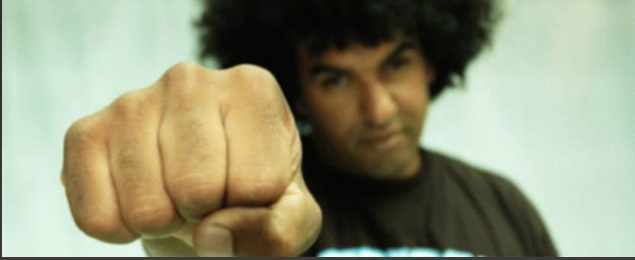

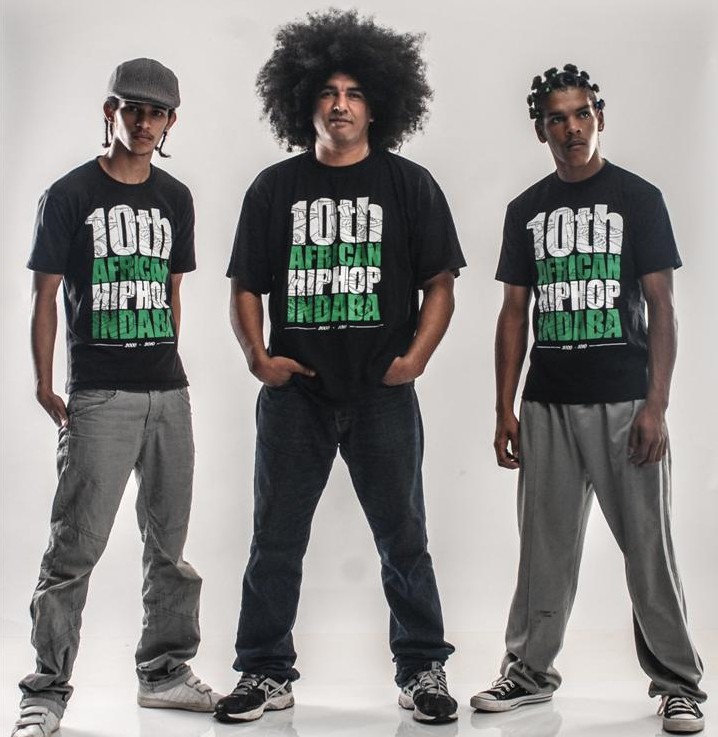

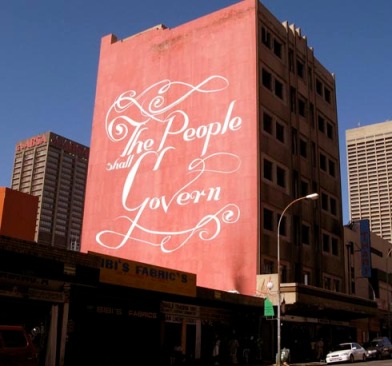

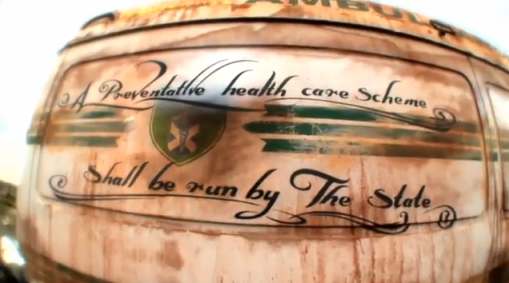

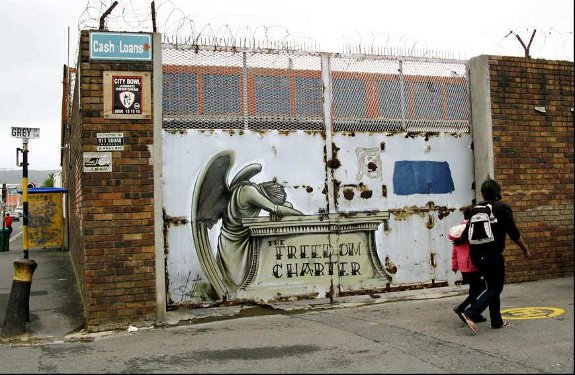

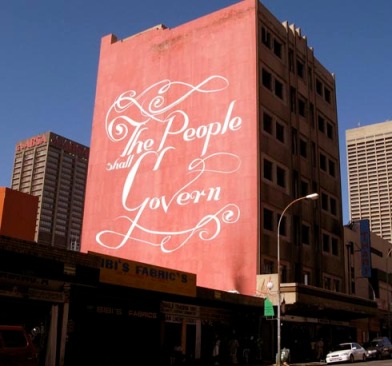

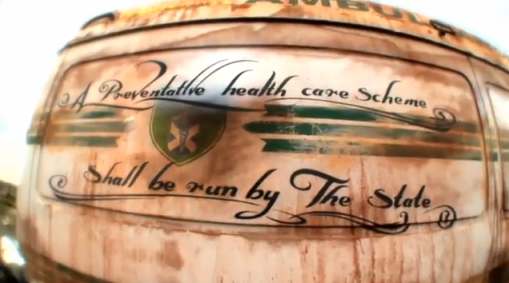

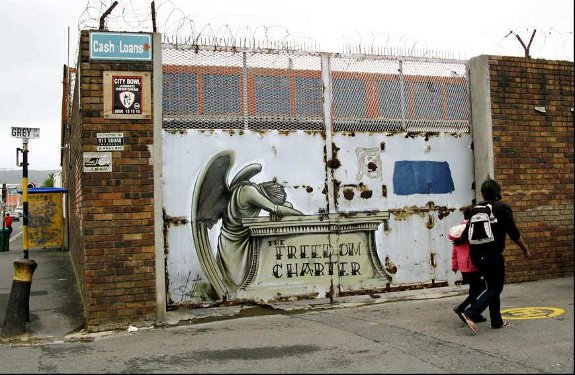

Naomi Klein asked many of these questions, exploring information about the handover of power that is often overlooked in discussions about South Africa’s modern struggle. Below is a condensed excerpt from Klein’s The Shock Doctrine in which she contemplates the legacy of the Freedom Charter, accompanied by photos from Faith47’s incredible Freedom Charter series:

“In January 1990, Nelson Mandela, age seventy-one, sat down in his prison compound to write a note to his supporters outside. It was meant to settle a debate over whether twenty-seven years behind bars, most of it spent on Robben Island off the coast of Cape Town, had weakened the leader’s commitment to the economic transformation of South Africa’s apartheid state. The note was only two sentences long, and it decisively put the matter to rest: “The nationalisation of the mines, banks and monopoly industries is the policy of the ANC, and the change or modification of our views in this regard is inconceivable. Black economic empowerment is a goal we fully support and encourage, but in our situation state control of certain sectors of the economy is unavoidable.”3

History, it turned out, was not over just yet, as Fukuyama had claimed. In South Africa, the largest economy on the African continent, it seemed that some people still believed that freedom included the right to reclaim and redistribute their oppressors’ ill-gotten gains.

That belief had formed the basis of the policy of the African National Congress for thirty-five years, ever since it was spelled out in its statement of core principles, the Freedom Charter…The process began in 1955, when the party dispatched fifty thousand volunteers into the townships and countryside. The task of the volunteers was to collect “freedom demands” from the people—their vision of a post-apartheid world in which all South Africans had equal rights. The demands were handwritten on scraps of paper: “Land to be given to all landless people,” “Living wages and shorter hours of work,” “Free and compulsory education, irrespective of colour, race or nationality,” “The right to reside and move about freely” and many more.4 When the demands came back, leaders of the African National Congress synthesized them into a final document, which was officially adopted on June 26, 1955, at the Congress of the People, held in Kliptown, a “buffer zone” township built to protect the white residents of Johannesburg from the teeming masses of Soweto. Roughly three thousand delegates— black, Indian, “coloured” and a few white—sat together in an empty field to vote on the contents of the document. According to Nelson Mandela’s account of the historic Kliptown gathering, “the charter was read aloud, section by section, to the people in English, Sesotho and Xhosa. After each section, the crowd shouted its approval with cries of ‘Afrika!’ and ‘Mayibuye!’”5 The first defiant demand of the Freedom Charter reads, “The People Shall Govern!”

…What the Freedom Charter asserted was the baseline consensus in the liberation movement that freedom would not come merely when blacks took control of the state but when the wealth of the land that had been illegitimately confiscated was reclaimed and redistributed to the society as a whole. South Africa could no longer be a country with Californian living standards for whites and Congolese living standards for blacks, as the country was described during the apartheid years; freedom meant that it would have to find something in the middle.

That was what Mandela was confirming with his two-sentence note from prison: he still believed in the bottom line that there would be no freedom without redistribution. With so many other countries now also “in transition,” it was a statement with enormous implications. If Mandela led the ANC to power and nationalized the banks and the mines, the precedent would make it far more difficult for Chicago School economists to dismiss such proposals in other countries as relics of the past and insist that only unfettered free markets and free trade had the ability to redress deep inequalities.

On February 11, 1990, two weeks after writing that note, Mandela walked out of prison a free man, as close to a living saint as existed anywhere in the world. South Africa’s townships exploded in celebration and renewed conviction that nothing could stop the struggle for liberation. Unlike the movement in Eastern Europe, South Africa’s was not beaten down but a movement on a roll. Mandela, for his part, was suffering from such an epic case of culture shock that he mistook a camera microphone for “some newfangled weapon developed while I was in prison.”8

The ANC went into negotiations with the ruling National Party determined to avoid the kind of nightmare that neighbouring Mozambique had experienced when the independence movement forced an end to Portuguese colonial rule in 1975. On their way out the door, the Portuguese threw a vindictive temper tantrum, pouring cement down elevator shafts, smashing tractors and stripping the country of all they could carry. To its enormous credit, the ANC did negotiate a relatively peaceful handover. However, it did not manage to prevent South Africa’s apartheid-era rulers from wreaking havoc on their way out the door. Unlike their counterparts in Mozambique, the National Party didn’t pour concrete—their sabotage, equally crippling, was far subtler, and was all in the fine print of those historic negotiations.

The talks that hashed out the terms of apartheid’s end took place on two parallel tracks that often intersected: one was political, the other economic. Most of the attention, naturally, focused on the high-profile political summits between Nelson Mandela and F.W. de Klerk, leader of the National Party.

De Klerk’s strategy in these negotiations was to preserve as much power as possible. He tried everything—breaking the country into a federation,

guaranteeing veto power for minority parties, reserving a certain percentage of the seats in government structures for each ethnic group—anything to prevent simple majority rule, which he was sure would lead to mass land expropriations and the nationalizing of corporations. As Mandela later put it, “What the National Party was trying to do was to maintain white supremacy with our consent.” De Klerk had guns and money behind him, but his opponent had a movement of millions. Mandela and his chief negotiator, Cyril Ramaphosa, won on almost every count.9 …

Running alongside these often explosive summits were the much lower profile economic negotiations, primarily managed on the ANC side by Thabo Mbeki, then a rising star in the party…South Africa’s whites had failed to keep blacks from taking over the government, but when it came to safeguarding the wealth they had amassed under apartheid, they would not give up so easily.

In these talks, the de Klerk government had a twofold strategy. First, drawing on the ascendant Washington Consensus that there was now only one way to run an economy, it portrayed key sectors of economic decision making—such as trade policy and the central bank—as “technical” or “administrative.” Then it used a wide range of new policy tools—international trade agreements, innovations in constitutional law and structural adjustment programs—to hand control of those power centres to supposedly impartial experts, economists and officials from the IMF, the World Bank, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the National Party—anyone except the liberation fighters from the ANC. It was a strategy of balkanization, not of the country’s geography (as de Klerk had originally attempted) but of its economy.

This plan was successfully executed under the noses of ANC leaders, who were naturally preoccupied with winning the battle to control Parliament. In the process, the ANC failed to protect itself against a far more insidious strategy—in essence, an elaborate insurance plan against the economic clauses in the Freedom Charter ever becoming law in South Africa. “The people shall govern!” would soon become a reality, but the sphere over which they would govern was shrinking fast…

“We were caught completely off guard,” recalled Padayachee, now in his early fifties. He had done his graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. He knew that at the time, even among free-market economists in the U.S., central bank independence was considered a fringe idea, a pet policy of a handful of Chicago School ideologues who believed that central banks should be run as sovereign republics within states, out of reach of the meddling hands of elected lawmakers.*,10 For Padayachee and his colleagues, who strongly believed that monetary policy needed to serve the new government’s “big goals of growth, employment and redistribution,” the ANC’s position was a no-brainer: “There was not going to be an independent central bank in South Africa…”

Padayachee and a colleague stayed up all night writing a paper that gave the negotiating team the arguments it needed to resist this curveball from the National Party. If the central bank (in South Africa called the Reserve Bank) was run separately from the rest of the government, it could restrict the ANC’s ability to keep the promises in the Freedom Charter. Besides, if the central bank was not accountable to the ANC government, to whom, exactly, would it be accountable? The IMF? The Johannesburg Stock Exchange? Obviously, the National Party was trying to find a backdoor way to hold on to power even after it lost the elections—a strategy that needed to be resisted at all costs. “They were locking in as much as possible,” Padayachee recalled. “That was a clear part of the agenda.”

Padayachee faxed the paper in the morning and didn’t hear back for weeks. “Then, when we asked what happened, we were told, ‘Well, we gave that one up.’” Not only would the central bank be run as an autonomous entity within the South African state, with its independence enshrined in the new constitution, but it would be headed by the same man who ran it under apartheid, Chris Stals. It wasn’t just the central bank that the ANC had given up: in another major concession, Derek Keyes, the white finance minister under apartheid, would also remain in his post—much as the finance ministers and central bank heads from Argentina’s dictatorship somehow managed to get their jobs back under democracy. The New York Times praised Keyes as “the country’s ranking apostle of low-spending business-friendly government.”11…

What happened in those negotiations is that the ANC found itself caught in a new kind of web, one made of arcane rules and regulations, all designed to confine and constrain the power of elected leaders. As the web descended on the country, only a few people even noticed it was there, but when the new government came to power and tried to move freely, to give its voters the tangible benefits of liberation they expected and thought they had voted for, the strands of the web tightened and the administration discovered that its powers were tightly bound. Patrick Bond, who worked as an economic adviser in Mandela’s office during the first years of ANC rule, recalls that the in-house quip was “Hey, we’ve got the state, where’s the power?” As the new government attempted to make tangible the dreams of the Freedom Charter, it discovered that the power was elsewhere.

Want to redistribute land? Impossible—at the last minute, the negotiators agreed to add a clause to the new constitution that protects all private property, making land reform virtually impossible. Want to create jobs for millions of unemployed workers? Can’t—hundreds of factories were actually about to close because the ANC had signed on to the GATT, the precursor to the World Trade Organization, which made it illegal to subsidize the auto plants and textile factories. Want to get free AIDS drugs to the townships, where the disease is spreading with terrifying speed? That violates an intellectual property rights commitment under the WTO, which the ANC joined with no public debate as a continuation of the GATT. Need money to build more and larger houses for the poor and to bring free electricity to the townships? Sorry—the budget is being eaten up servicing the massive debt, passed on quietly by the apartheid government. Print more money? Tell that to the apartheid-era head of the central bank. Free water for all? Not likely. The World Bank, with its large in-country contingent of economists, researchers and trainers (a self-proclaimed “Knowledge Bank”), is making private-sector partnerships the service norm. Want to impose currency controls to guard against wild speculation? That would violate the $850 million IMF deal, signed, conveniently enough, right before the elections. Raise the minimum wage to close the apartheid income gap? Nope. The IMF deal promises “wage restraint.”12 And don’t even think about ignoring these commitments— any change will be regarded as evidence of dangerous national untrustworthiness, a lack of commitment to “reform,” an absence of a “rules-based system.” All of which will lead to currency crashes, aid cuts and capital flight. The bottom line was that South Africa was free but simultaneously captured; each one of these arcane acronyms represented a different thread in the web that pinned down the limbs of the new government.

Want to redistribute land? Impossible—at the last minute, the negotiators agreed to add a clause to the new constitution that protects all private property, making land reform virtually impossible. Want to create jobs for millions of unemployed workers? Can’t—hundreds of factories were actually about to close because the ANC had signed on to the GATT, the precursor to the World Trade Organization, which made it illegal to subsidize the auto plants and textile factories. Want to get free AIDS drugs to the townships, where the disease is spreading with terrifying speed? That violates an intellectual property rights commitment under the WTO, which the ANC joined with no public debate as a continuation of the GATT. Need money to build more and larger houses for the poor and to bring free electricity to the townships? Sorry—the budget is being eaten up servicing the massive debt, passed on quietly by the apartheid government. Print more money? Tell that to the apartheid-era head of the central bank. Free water for all? Not likely. The World Bank, with its large in-country contingent of economists, researchers and trainers (a self-proclaimed “Knowledge Bank”), is making private-sector partnerships the service norm. Want to impose currency controls to guard against wild speculation? That would violate the $850 million IMF deal, signed, conveniently enough, right before the elections. Raise the minimum wage to close the apartheid income gap? Nope. The IMF deal promises “wage restraint.”12 And don’t even think about ignoring these commitments— any change will be regarded as evidence of dangerous national untrustworthiness, a lack of commitment to “reform,” an absence of a “rules-based system.” All of which will lead to currency crashes, aid cuts and capital flight. The bottom line was that South Africa was free but simultaneously captured; each one of these arcane acronyms represented a different thread in the web that pinned down the limbs of the new government.

A long-time anti-apartheid activist, Rassool Snyman, described the trap to me in stark terms. “They never freed us. They only took the chain from around our neck and put it on our ankles.” Yasmin Sooka, a prominent South African human rights activist, told me that the transition “was business saying, ‘We’ll keep everything and you [the ANC] will rule in name. . . . You can have political power, you can have the façade of governing, but the real governance will take place somewhere else.’” †, 13 It was a process of infantilization that is common to so-called transitional countries—new governments are, in effect, given the keys to the house but not the combination to the safe…

In the first two years of ANC rule, the party still tried to use the limited resources it had to make good on the promise of redistribution. There was a flurry of public investment—more than a hundred thousand homes were built for the poor, and millions were hooked up to water, electricity and phone lines.14 But, in a familiar story, weighed down by debt and under international pressure to privatize these services, the government soon began raising prices. After a decade of ANC rule, millions of people had been cut off from newly connected water and electricity because they couldn’t pay the bills. ‡ At least 40 percent of the new phones lines were no longer in service by 2003.15 As for the “banks, mines and monopoly industry” that Mandela had pledged to nationalize, they remained firmly in the hands of the same four white-owned mega-conglomerates that also control 80 percent of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange.16 In 2005, only 4 percent of the companies listed on the exchange were owned or controlled by blacks.17 Seventy percent of South Africa’s land, in 2006, was still monopolized by whites, who are just 10 percent of the population.18 Most distressingly, the ANC government has spent far more time denying the severity of the AIDS crisis than getting lifesaving drugs to the approximately 5 million people infected with HIV, though there were, by early 2007, some positive signs of progress.19 Perhaps the most striking statistic is this one: since 1990, the year Mandela left prison, the average life expectancy for South Africans has dropped by thirteen years.20

Underlying all these facts and figures is a fateful choice made by the ANC after the leadership realized it had been outmanoeuvred in the economic negotiations. At that point, the party could have attempted to launch a second liberation movement and break free of the asphyxiating web that had been spun during the transition. Or it could simply accept its restricted power and embrace the new economic order. The ANC’s leadership chose the second option. Rather than making the centrepiece of its policy the redistribution of wealth that was already in the country— the core of the Freedom Charter on which it had been elected—the ANC, once it because the government, accepted the dominant logic that its only hope was to pursue new foreign investors who would create new wealth, the benefits of which would trickle down to the poor. But for the trickle-down model to have a hope of working, the ANC government had to radically alter its behaviour to make itself appealing to investors.

This was not an easy task, as Mandela had learned when he walked out of prison. As soon as he was released, the South African stock market collapsed in panic; South Africa’s currency, the rand, dropped by 10 percent.21 A few weeks later, De Beers, the diamond corporation, moved its headquarters from South Africa to Switzerland.22 This kind of instant punishment from the markets would have been unimaginable three decades earlier, when Mandela was first imprisoned. In the sixties, it was unheard of for multinationals to switch nationalities on a whim and, back then, the world money system was still firmly linked to the gold standard. Now South Africa’s currency had been stripped of controls, trade barriers were down, and most trading was short-term speculation.

Not only did the volatile market not like the idea of a liberated Mandela, but just a few misplaced words from him or his fellow ANC leaders could lead to an earth-shaking stampede by what the New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman has aptly termed “the electronic herd.”23 The stampede that greeted Mandela’s release was just the start of what became a call-and-response between the ANC leadership and the financial markets—a shock dialogue that trained the party in the new rules of the game. Every time a top party official said something that hinted that the ominous Freedom Charter might still become policy, the market responded with a shock, sending the rand into free fall. The rules were simple and crude, the electronic equivalent of monosyllabic grunts: justice—expensive, sell; status quo—good, buy. When, shortly after his release, Mandela once again spoke out in favour of nationalization at a private lunch with leading businessmen, “the All-Gold Index plunged by 5 per cent.”24

Even moves that seemed to have nothing to do with the financial world but betrayed some latent radicalism seemed to provoke a market jolt. When Trevor Manuel, an ANC minister, called rugby in South Africa a “white minority game” because its team was an all-white one, the rand took another hit.25

…Rather than calling for the nationalization of the mines, Mandela and Mbeki began meeting regularly with Harry Oppenheimer, former chairman of the mining giants Anglo- American and De Beers, the economic symbols of apartheid rule. Shortly after the 1994 election, they even submitted the ANC’s economic program to Oppenheimer for approval and made several key revisions to address his concerns, as well as those of other top industrialists.

28 Hoping to avoid getting another shock from the market, Mandela, in his first post-election interview as president, carefully distanced himself from his previous statements favouring nationalization. “In our economic policies . . . there is not a single reference to things like nationalization, and this is not accidental,” he said. “There is not a single slogan that will connect us with any Marxist ideology.” §, 29 The financial press offered steady encouragement for this conversion: “Though the ANC still has a powerful leftist wing,” the Wall Street Journal observed, “Mr. Mandela has in recent days sounded more like Margaret Thatcher than the socialist revolutionary he was once thought to be.”30

The memory of its radical past still clung to the ANC, and despite the new government’s best efforts to appear unthreatening, the market kept inflicting its painful shocks: in a single month in 1996, the rand dropped 20 percent, and the country continued to hemorrhage capital as South Africa’s jittery rich moved their money offshore.31

…In South Africa only a handful of Mbeki’s closest colleagues even knew that a new economic program was in the works, one very different from the promises they had all made during the 1994 elections. Of the people on the team, Gumede writes, “all were sworn to secrecy and the entire process was shrouded in deepest confidentiality lest the left wing get wind of Mbeki’s plan.”

…In June 1996, Mbeki unveiled the results: it was a neo-liberal shock therapy program for South Africa, calling for more privatization, cutbacks to government spending, labour “flexibility,” freer trade and even looser controls on money flows. According to Gelb, its overriding aim “was to signal to potential investors the government’s (and specifically the ANC’s) commitment to the prevailing orthodoxy.”34 To make sure the message was loud and clear to traders in New York and London, at the public launch of the plan, Mbeki quipped, “Just call me a Thatcherite.”35

Shock therapy is always a market performance—that is part of its underlying theory. The stock market loves overhyped, highly managed moments that send stock prices soaring, usually provided by an initial public stock offering, the announcement of a huge merger or the hiring of a celebrity CEO. When economists urge countries to announce a sweeping shock therapy package, the advice is partially based on an attempt to imitate this kind of high-drama market event and trigger a stampede—but rather than selling an individual stock, they are selling a country. The hoped-for response is “Buy Argentine stocks!” “Buy Bolivian bonds!” A slower, more careful approach, on the other hand, may be less brutal, but it deprives the market of these hype-bubbles, during which the real money gets made. Shock therapy is always a significant gamble, and in South Africa it didn’t work: Mbeki’s grand gesture failed to attract long-term investment; it resulted only in speculative betting that ended up devaluing the currency even further…

Some commissioners felt that multinational corporations that had benefited from apartheid should be forced to pay reparations. In the end the Truth and Reconciliation Commission made the modest recommendation of a one-time 1 percent corporate tax to raise money for the victims, what it called “a solidarity tax.” Sooka expected support for this mild recommendation from the ANC; instead, the government, then headed by Mbeki, rejected any suggestion of corporate reparations or a solidarity tax, fearing that it would send an anti-business message to the market. “The president decided not to hold business accountable,” Sooka told me. “It was that simple.” In the end, the government put forward a fraction of what had been requested, taking the money out of its own budget, as the commissioners had feared.

South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is frequently held up as a model of successful “peace building,” exported to other conflict zones from Sri Lanka to Afghanistan. But many of those who were directly involved in the process are deeply ambivalent. When he unveiled the final report in March 2003, the commission’s chairman, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, confronted journalists with freedom’s unfinished business. “Can you explain how a black person wakes up in a squalid ghetto today, almost 10 years after freedom? Then he goes to work in town, which is still largely white, in palatial homes. And at the end of the day, he goes back home to squalor? I don’t know why those people don’t just say, ‘To hell with peace. To hell with Tutu and the truth commission.’”36

“The fact that the ANC dismissed the Commission’s call for corporate reparations is particularly unfair, Sooka pointed out, because the government continues to pay the apartheid debt. In the first years after the handover, it cost the new government 30 billion rand annually (about $4.5 billion) in servicing—a sum that provides a stark contrast with the paltry total of $85 million that the government ultimately paid out to more than nineteen thousand victims of apartheid killings and torture and their families. Nelson Mandela has cited the debt burden as the single greatest obstacle to keeping the promises of the Freedom Charter. “That is 30 billion [rand] we did not have to build houses as we planned, before we came into government, to make sure that our children go to the best schools, that unemployment is properly addressed and that everybody has the dignity of having a job, a decent income, of being able to provide shelter to his beloved, to feed them. . . . We are limited by the debt that we inherited.”37

…What makes the ANC’s decision to keep paying the debt so infuriating to activists like Brutus is the tangible sacrifice made to meet each payment. For instance, between 1997 and 2004, the South African government sold eighteen state-owned firms, raising $4 billion, but almost half the money went to servicing the debt.38 In other words, not only did the ANC renege on Mandela’s original pledge of “the nationalisation of the mines, banks and monopoly industry” but because of the debt, it was doing the opposite—selling off national assets to make good on the debts of its oppressors.

Then there is the matter of where, precisely, the money is going. During the transition negotiations, F.W. de Klerk’s team demanded that all civil servants be guaranteed their jobs even after the handover; those who wanted to leave, they argued, should receive hefty lifelong pensions. This was an extraordinary demand in a country with no social safety net to speak of, yet it was one of several “technical” issues on which the ANC ceded ground.39 The concession meant that the new ANC government carried the cost of two governments— its own, and a shadow white government that was out of power. Forty percent of the government’s annual debt payments go to the country’s massive pension fund. The vast majority of the beneficiaries are former apartheid employees.**, 40

In the end, South Africa has wound up with a twisted case of reparations in reverse, with the white businesses that reaped enormous profits from black labour during the apartheid years paying not a cent in reparations, but the victims of apartheid continuing to send large paycheques to their former victimizers. And how do they raise the money for this generosity? By stripping the state of its assets through privatization—a modern form of the very looting that the ANC had been so intent on avoiding when it agreed to negotiations, hoping to prevent a repeat of Mozambique. Unlike what happened in Mozambique, however, where civil servants broke machinery, stuffed their pockets and then fled, in South Africa the dismantling of the state and the pillaging of its coffers continue to this day.”

– Naomi Klein, Democracy Born in Chains